So I’ll probably get hugely humiliated by writing this post – but then again, how do we learn without failing…

I today had the chance to watch DJ Adams run through one of his #HandsOnSAPDev live streams: (it start’s 3mins 30secs in if you want to watch)

It was an interesting watch and makes me long for those days when I could just play with APIs marked beta and hope to get away with not having to do a massive code re-write several months later.

Anyway – during the episode, DJ was using the “standard” OAuth Client Credentials flow and I had to ask myself – “Why is this any more secure than just using basic authentication?”

I tried to put the point to DJ – but there’s only so much one can do in a chat window, hence this post.

I have since tried to do a little research on the topic – and found this rather good Stack Exchange discussion on the topic:

https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/297997/369892

Both the question and answer made a lot of sense – read if you like – but I’ll work through the points – in my own style – which is to illustrate with bad drawings.

OAuth Client Credential Flow explained with bad drawings

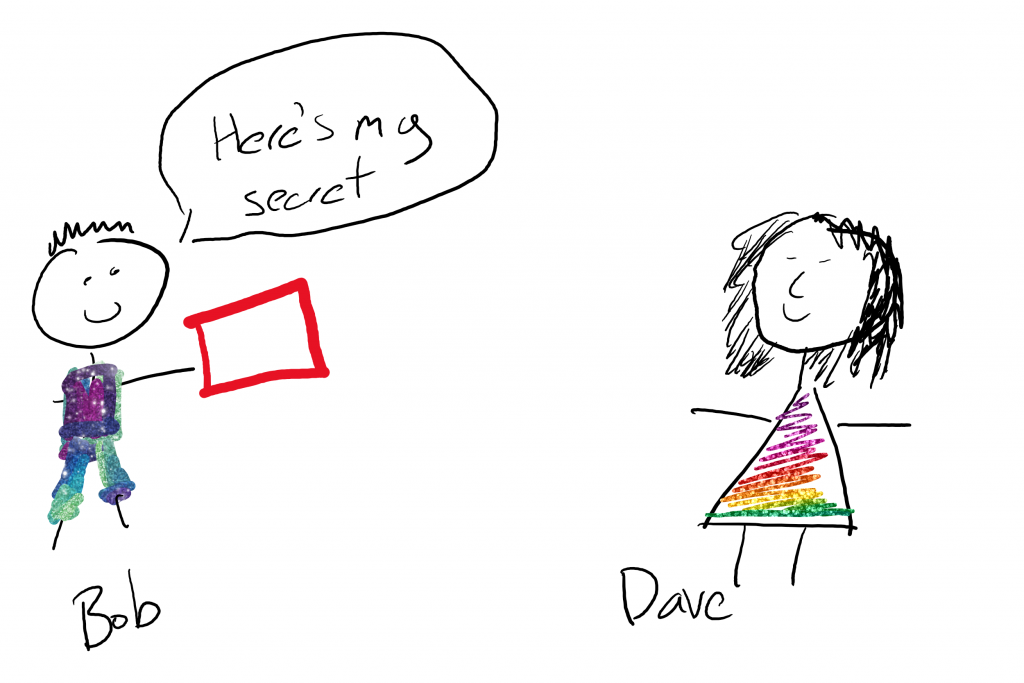

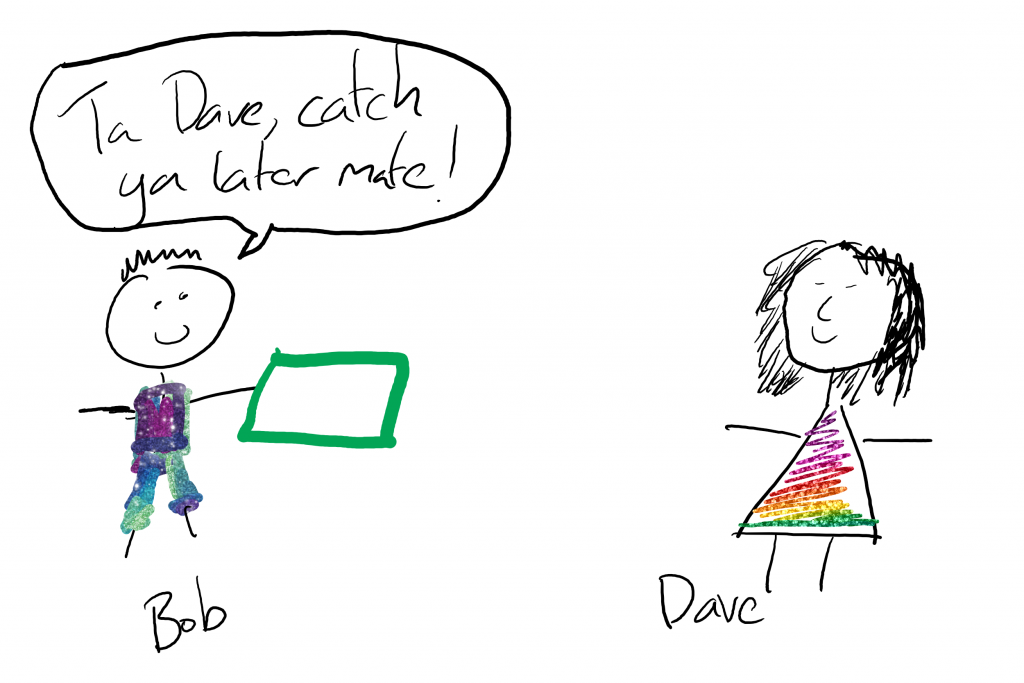

In the OAuth Client Credentials flow – one system (Bob, our client) gives another system (Dave, our authorisation server) his special secret key.

Bob uses his secret key to authenticate himself to the authorisation server. In the example DJ worked through authentication was in form of an authorisation header with <clientid>:<clientsecret>. (And a body that contained the user’s username and password – this is useful for API’s that need to pickup a given user’s credential.) Note that nothing here is encrypted beyond the usual transport encryption. I’ve seen many implementation of this process where the username isn’t actually needed because the particular client id and secret are associated with a particular system user. (I’ve never seen any other one where the user’s password is needed – noting these API’s are beta!).

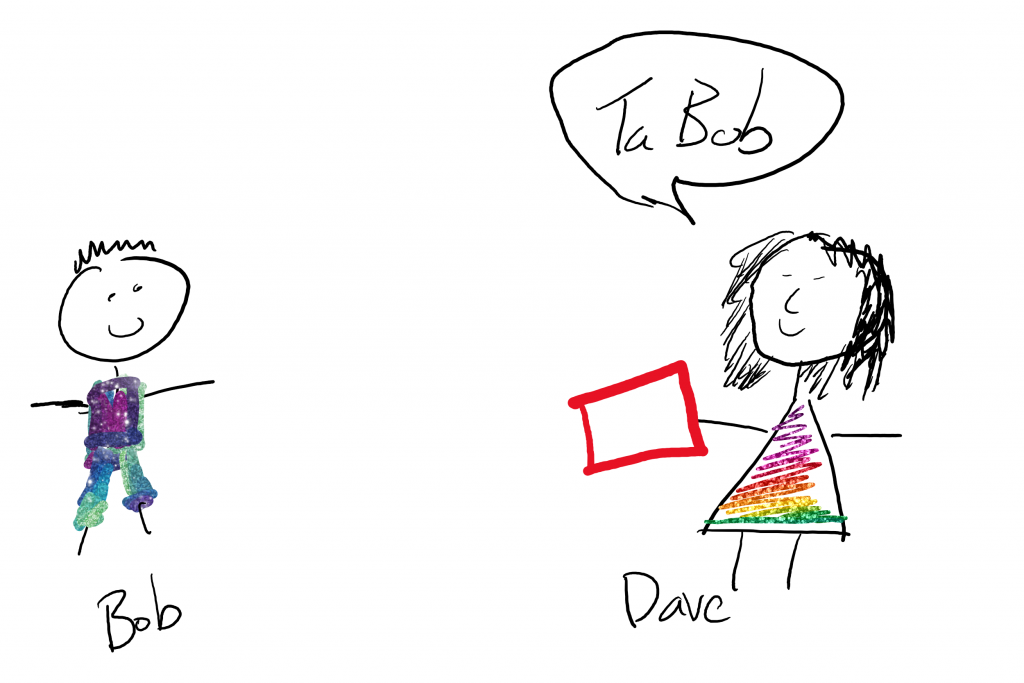

Once Dave (our authorisation server) gets our secret, he checks it is still valid (kinda like checking a password… no wait, exactly like checking a password) and then gives us a limited lifetime token to use the API. In the example DJ worked through it also checked the username and password – strange, but hey why not? (Other than it being a TERRIBLE idea that any server should need to store a user’s password as well as client id and secret!)

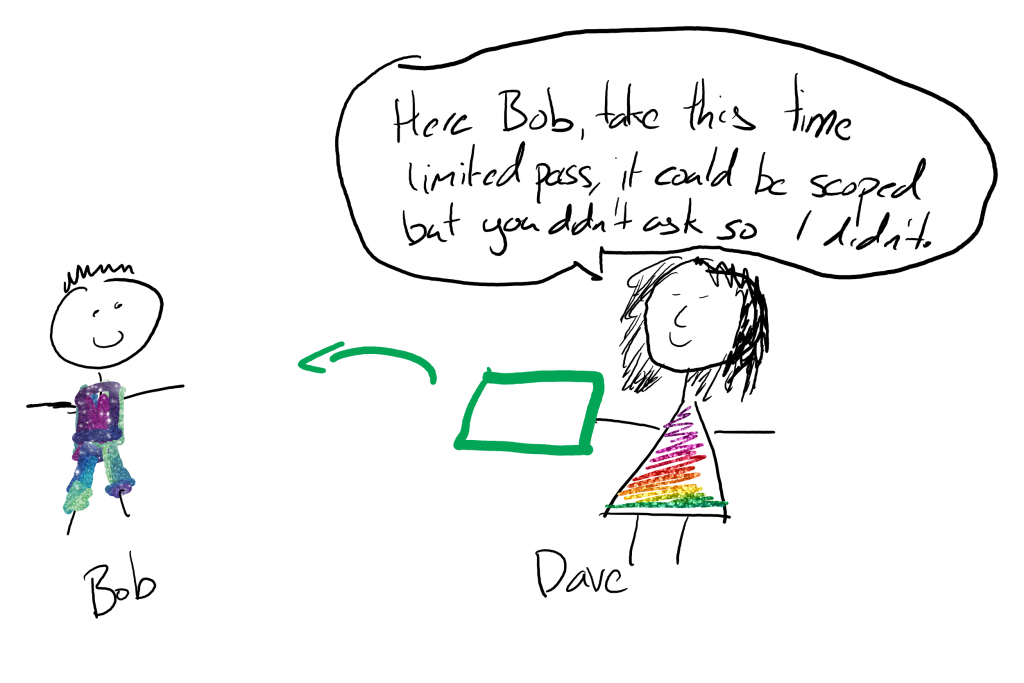

Now, according to the OAuth standards, Bob could have asked for the token he picked up to be scoped to only allow certain access. But because Bob is a little bit lazy and Dave doesn’t insist that he asks for scope, Bob never does. If you got to the oauth.com website and check out the client credential flow (https://www.oauth.com/oauth2-servers/access-tokens/client-credentials/_ you’ll even see they mention that hardly anyone ever uses scope in the flow.

Your service can support different scopes for the client credentials grant. In practice, not many services actually support this.

OAuth.com

Plus Bob likes reducing his interactions with Dave to make things faster, so one token to rule them all is far easier and more generic. Bob might be a programmer (if he weren’t a system… stick with the metaphors people!)

Bob now has his limited lifetime access token he can use to authorise the API interactions. So he goes to make call to the API server.

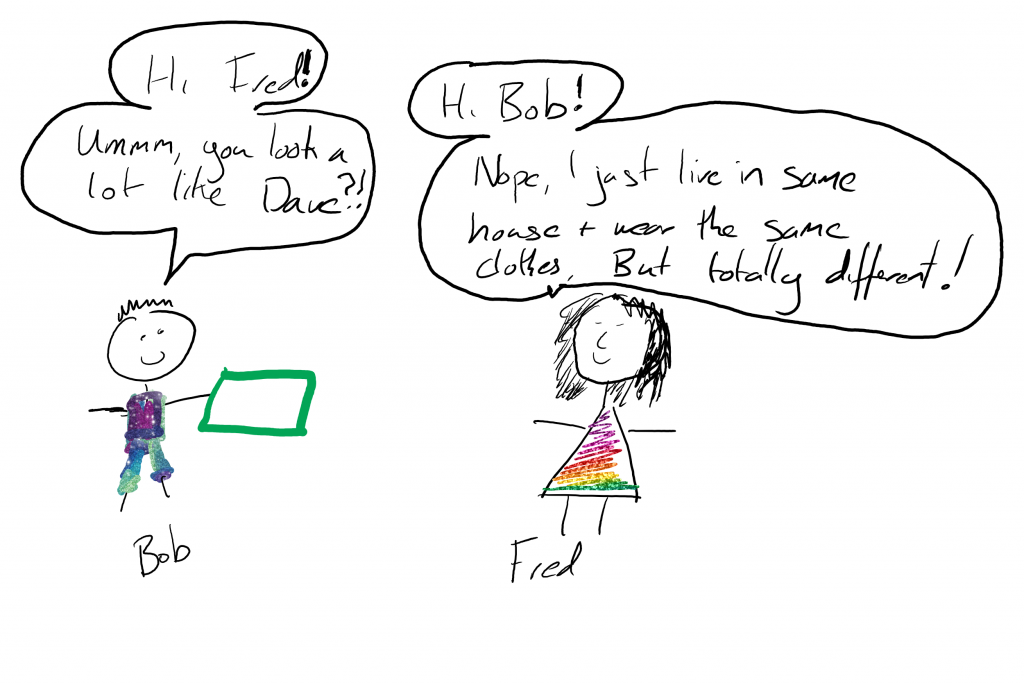

Imagine Bob’s surprise when talking to the API server it looks very very much like Dave. But it’s not Dave, it’s Fred the API server. In DJ’s example the authentication server was accountblah.authentication.region.hana.ondemand.com and the API server was accounts-service.cfapps.region.hana.ondemand.com. Slightly different names – and actually resolve to different IP addresses too! But if I look at the SuccessFactors implementation of this similar token logic – both sit on same server (from an external view – who knows or cares what happens internally). Anyway – Bob uses his token to request some data from Fred.

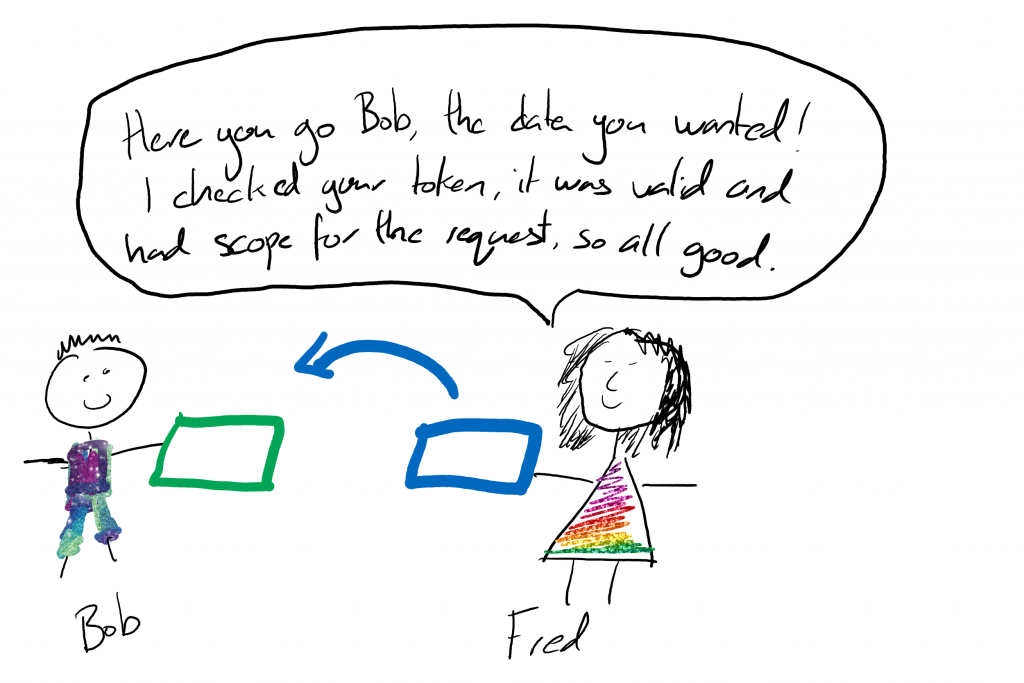

Fred then goes away and checks that the token is valid. When the token is sent over to Fred, it’s not encrypted in any way or signed with a special key or anything. In DJ’s example it was just in the Authorisation header as “Bearer <access token>”. The security of this exchange was relying on the transport encryption – just like the original request to get the access token.

Fred may well be wondering if Bob is ever going to send him a request he doesn’t have scope for, might need to have a chat to Dave about that… But he validates that Bob has a token that is still valid and that is valid for the requested action (get list of sub-accounts for example.)

So what makes this more secure?

In the exchange I just documented, I cannot see how taking the extra step to pick up an access token to call Fred has made the exchange between Bob and Fred more secure… The only things I can think of are:

- Conversations to Dave (the authentication server) are treated more seriously, we take extra special care to not record them or allow anyone to snoop on them because the client secret is long lived (like a password).

- Possibly means that if we take less care that conversations with Fred leak then the impact will be short lived due to the token expiring sooner.

- yep – that’s about it.

- can’t think of anything else.

Frankly – for the increase in hassle I’m not seeing an ROI on securing my API calls. Especially as for many implementations of this sort of logic the token API runs on same server as the main application API. (Dave == Fred)

What makes this useful then?

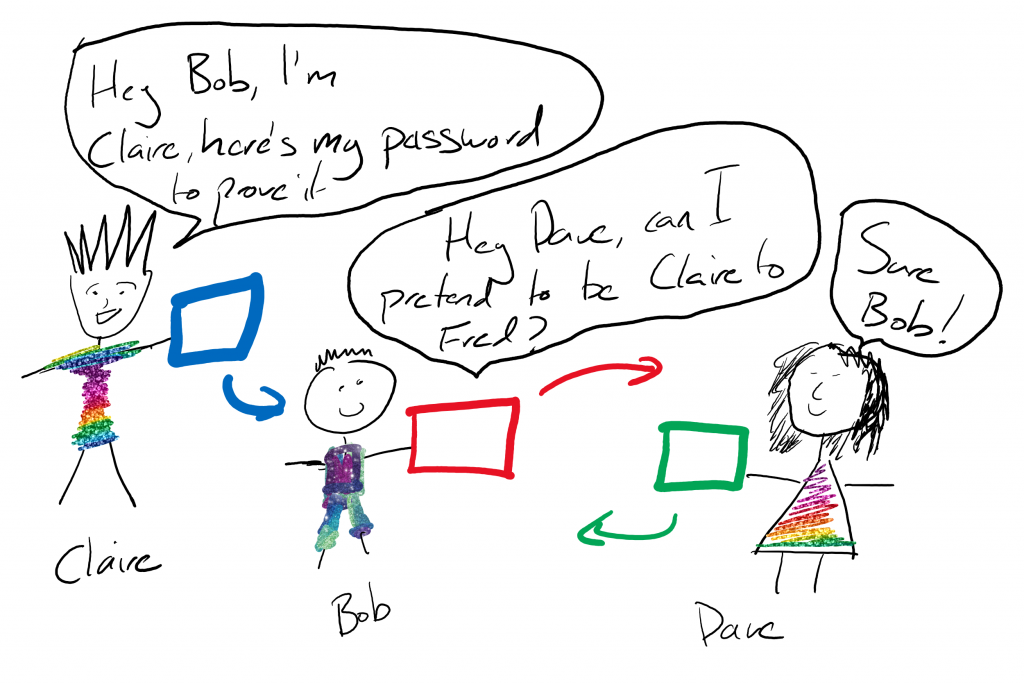

This is different thing – and goes to identity rather than authorisation. With the client credential approach I can config my calls to the API server to be treated as if one of the system users is making the call and not a generic API user. I have one password that I use to get access tokens that allow me to “pretend” to be any user I want to be for the purpose of fetching/updating data via the API. This is something that I would use all the time in SuccessFactors* – it lets me query data using the user’s permissions. Very useful! SAPCP is set up to do this. I believe this is how, for example applications running on SAPCP can use OAuth Bearer destinations to access API calls as per the logged in user – even though the user is not logged in to that remote application. We can’t do lots of client side SSO, because browsers have gotten wise to applications doing SSO to remote system inside frames (SSO to a remote server requires JS running on different domains generally and falls foul of Single Origin restrictions). So solutions like SAP Cloud Portal and now SAP WorkZone use the SAPCP destination service to call OAuth Client Credential flows to get access tokens as per the person that is logged into their solution. Obviously this requires trust set up – which is the the client id and secret.

So Claire (an actual person, not a system for once) comes along and asks Bob (the system) for some data that’s on the system that is Fred (are you lost yet?). Bob asks Dave for an access token that will allow him to ask Fred for stuff on behalf of Claire. Dave, being ever so obliging and having verified the client id and secret, then gives Bob a temp pass to pretend to be Claire when speaking to Fred.

Okay if you’re following that, you’re doing well. But really – that’s why we use these credentials. It has nothing to do with security and everything to do with making life easier for system to system communication when pretending to be other people.

* Now to explain that aster a bit up the page. I would possibly use this logic in SuccessFactors, but I don’t because it requires that the user that “Bob” is pretending to be needs to have API access or Fred refuses the call. Giving all users API access is not a good idea at the moment in SuccessFactors because of the way that certain fields tend not to be hidden or controlled in API access compared to front end access.

Summary

So, to summarise, I cannot see any real security benefit to using OAuth Client Credential flows over Basic Auth unless you are looking to distribute your development spend on making one area of your codebase more secure than others. Even then it’s not that much better. If you’re able to intercept and abuse a basic authentication flow, you’d be just as likely to be able to intercept and abuse an OAuth Client Credential flow. Indeed because organisations tend to use the Client Credential flow as per the example DJ had (with the credential applying to a given user) or like SuccessFactors does, it actually open up a whole new security issue… It’s not just one “user” that might have their credentials breached, it’s anyone that the system is allowed to impersonate.

Okay – go at me – I’ve missed something – else we wouldn’t be using OAuth Client Credentials for the sorts of API calls that DJ was making in the video.

I note there are many other OAuth flows and some of them are much more secure – they use PPK encryption to ensure that messages are signed and headers never could leak credentials like Basic Authentication can. But the client credential flow – hmmm this one, in the use case where it’s a single user, not “impersonating” anyone – there’s no benefit over Basic Auth and another communication round trip to have to deal with.